In case you missed it, ChatGPT is a Large Language Model (LLM) released by the non-profit-turned-$20B-company OpenAI in late 2022. With the appearance of a chatbot, ChatGPT can write essays, poetry, and e-mails, generate tables and strategies, as well as write and debug code in various languages including Python, JavaScript and HTML. Think of your Google search function but with unique expansive responses and a conversational style.

As a security scholar specialising in policy responses to misinformation and disinformation, I am particularly interested in understanding the risks that LLMs such as ChatGPT pose for information order, our complex global system of communication and knowledge. This article examines the five main risks that ChatGPT poses when it comes to information security.

Believing it's intelligent, when it's not

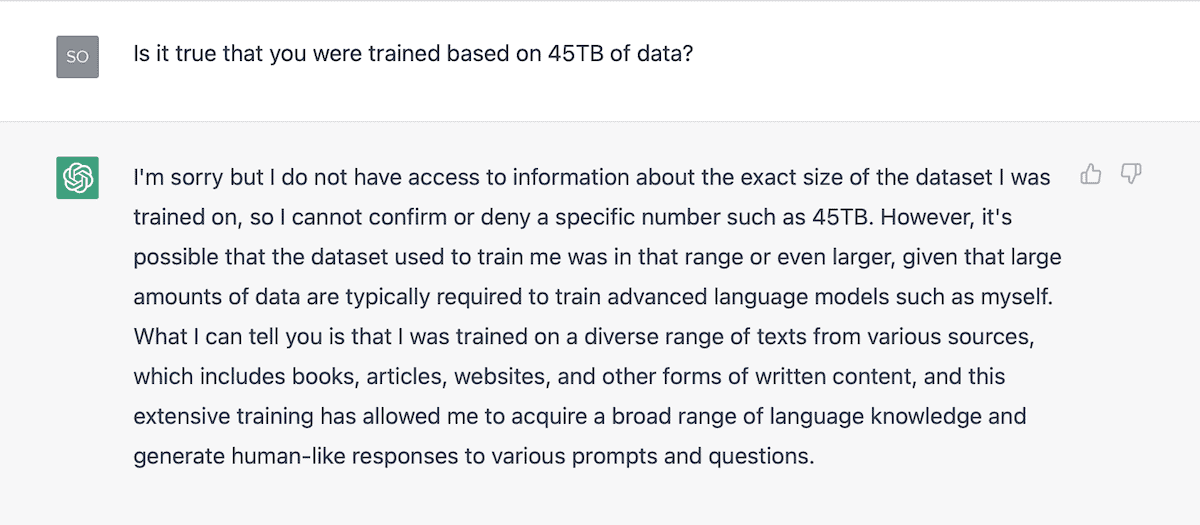

Just like other LLMs (e.g. BERT, GPT4, OPT), ChatGPT works by using information from the Internet — an estimated 45 terabytes of text data obtained from Wikipedia, Reddit, blogs, and virtually anything else publicly accessible. Whilst OpenAI has not disclosed the exact amount of data that was used to train ChatGPT, the model itself confirmed that the size of the dataset was “in that range or even larger”. That’s approximately 9 trillion words.

Based on this data, ChatGPT can predict what users want to read in response to their prompts. In other words, it is not trained to provide accurate answers, it is trained to provide statistically probable answers. For this reason, computational linguists and Google AI ethicists warned about “the dangers of stochastic parrots” already in 2021. LLMs regularly produce so-called “hallucinations” in their responses. “The model will confidently state things as if they were facts that are entirely made up.” explained OpenAI CEO Sam Altman in an interview.

Indeed, it is important to remember that LLMs are not intelligent machines. Nor or they sentient robots. They do not memorise information or provide critical reasoning, they simply predict which word goes after another. As a result, they can provide answers which, at first sight, sound totally plausible but will turn out to be completely incorrect. After an experiment using Artificial Intelligence (AI) to write news articles, US media CNET had to correct 41 of the 77 posts produced by LLMs. One can therefore only think of LLMs as sophisticated bullshitters.

“ChatGPT is not trained to provide accurate answers, it is trained to provide statistically probable answers.”

Princeton Computer Scientist Arvind Narayanan shared: ”There’s no question that these models are quickly getting better. But their ability to sound convincing is getting better just as quickly, which means that it’s actually getting harder for even experts to spot when they do make mistakes.” Indeed, a study conducted by NewsGuard, a company that rates the credibility of news and information online, showed that the newest version of ChatGPT produces misinformation more frequently and persuasively than before.

The first risk posed by LLMs for information order is thus thinking they are intelligent when they are not. We cannot receive information from ChatGPT at face value and should be extremely skeptical of any answer it provides.

Replicating human bias and discrimination

AI can only be as good as the humans who encode it. Expecting LLMs to be reliable sources, or even smarter than people, is therefore a misguided thought. Computers, machines, and AI-based models cannot act like a human brain, nor can they offer accurate representations of the world. LLMs assimilate the biases and discriminatory views of their coders and of existing data, therefore freezing information in the past and offering no prospect of progress.

ChatGPT being based on data freely available online, it is biased towards sources written in English, by white people, and by men — a representation of broader societal inequalities. In addition, LLMs are quick to replicate what’s already out there online: racism, homophobia, violence, and more. When Meta released its own LLM, Galactica, in November 2022, it promptly had to put it offline because of antisemitic and dangerous responses.

The idea of statistical models being dangerous tools to rely on is not new. In Weapons of Math Destruction, data scientist Cathy O’Neil builds on her experience working at a hedge fund during the financial crisis of 2008 to warn against the unfair and discriminatory features of mathematical models. They can exacerbate inequality, reinforce bias, and undermine democracy, ultimately harming the most vulnerable members of society.

Read Weapons of Math Destruction

Cathy O’Neil, author of Weapons of Math Destruction, has a PhD in mathematics and worked for a hedge fund during the 2008 financial crisis. She witnessed the impact of faulty mathematical models, which inspired her to become an advocate for ethical data science. In her book, O’Neil argues that many algorithms and big data models used in various industries are unfair and discriminatory, exacerbating inequality and harming society. She suggests ways to address these issues, such as increasing transparency and accountability in algorithmic decision-making.

Relying too heavily on algorithms and models such as ChatGPT for our decision-making is thus dangerous, both at an individual level and a societal level. It stops us from progressive thinking and replicates existing biases and discriminatory views.

Being used by malign actors

Since ChatGPT and other LLMs are publicly accessible, anyone with an internet connection and a laptop can use it. That includes malign actors, which sadly are more often than not quicker than others at seizing opportunities from technological advances. Actors with harmful intentions could thus easily use LLMs as a tool to expand their activities, wether they use them for redacting false reports sounding incredibly true or coding malware – although OpenAI’s policies technically prohibits it.

“I’m particularly worried that these models could be used for large-scale disinformation” confessed Sam Altman. Indeed, it would be very easy for individuals with low programming knowledge and skills to use ChatGPT to write computer code meant to launch offensive cyberattacks. “It’s still too early to decide whether or not ChatGPT capabilities will become the new favourite tool for participants in the Dark Web. However, the cybercriminal community has already shown significant interest and are jumping into this latest trend to generate malicious code.” wrote Check Point Research, an international cybersecurity company.

“With great power comes great responsibility”, as popularised by the Marvel fantasy world. But the consequences of LLMs being used by malign actors are very real and could pose serious threats to individual and structural security.

Data leaks and privacy issues

ChatGPT poses several important questions in terms of data protection. First, how safe are users’ personal data, especially the prompts they type into the chatbot? Second, how is the training data complying with privacy laws? “If you’ve ever written a blog post or product review, or commented on an article online, there’s a good chance this information was consumed by ChatGPT.” says Uri Gal, Professor in Business Information Systems at the University of Sydney.

Since LLMs using chatbots like ChatGPT process personal data (e.g. prompts), they must comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Under this set of rules — the toughest privacy and security law in the world, organisations must obtain explicit consent to collect and use personal data, as well as only do so for the stated purposes. So, is ChatGPT even legal? Well, that’s still to be determined.

On 22 March 2023, some conversations and prompts from ChatGPT were randomly leaked to other users — a clear breach of GDPR regulations. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman explained on Twitter they had a ”significant issue (…) due to a bug” after which some users were able to see the titles of other users’ conversation history. He added: “we feel awful about this”. I wonder how Data Protection Authorities will feel as well when they open a data infringement investigation. In Italy, ChatGPT was just banned for alleged privacy violations.

In sum, the risks in terms of data protection and privacy are potentially enormous. Whilst awaiting for further clarity on the matter, caution is in order. We should avoid inputing any personal or sensitive information into ChatGPT. In the meantime, OpenAI released a form for individuals to ask for the “corrections, access requests or transfers” of their data (that includes deleting it).

Big tech's power grab

In the development and governance of AI, big tech companies (e.g. Meta, Alphabet, Microsoft) have the upper hand. They largely determine the direction in which LLMs are developing, with public authorities only reactively responding to their advances. As a result, big tech also largely control the narrative that surrounds their actions. This poses risks for the information order as it influences public perceptions and behaviour in the field of AI.

Will AI replace us humans? Will AI take all our jobs? Behind the hype and the fear-mongering, very little evidence is available to show that AI would indeed be qualified and potent enough to replace human beings. Besides, as explained earlier, leaving decision-making in the hands of machines would halt us from progress, which only human brains, creativity, and imagination can trigger. In addition, this narrative is a camouflage for the real labor issue brought by ChatGPT and similar LLMs: the concentration of power in the hands of a few elites — big tech.

"The narrative of job losses is a camouflage for the real labor issue brought by ChatGPT and similar LLMs: the concentration of power in the hands of a few elites — big tech."

It is no secret that the large models were built with questionable ethical standards. From exploiting $2/hour workers in Kenya to firing employees who question their actions and users committing suicide, there are many obvious red flags in big tech’s development of generative AI. In addition, it appears impossible to study the training data used for ChatGPT because of the secrecy which big tech put on it behind the veil of corporate property or safety. Yet another black box algorithm exacerbating existing inequalities.

Above all, the appropriation of public knowledge and texts, as well as the tendency to favour fast-paced progress for profit and market leadership over careful development of technology, is what raises most alarm bells when it comes to big tech’s behaviour. When confronted to the recurring hallucinations of its chatbot, Microsoft explained those answers were “usefully wrong”. Useful? Useful for whom? Questioning who benefits from these accelerated technological experiments is only the first domino in a chain of alarming events.

So, what next?

In conclusion, ChatGPT and other similar LLMs pose several important risks when it comes to information order and security: overestimating intelligence, replicating human biases, usage by malign actors, data protection, as well as power imbalances. These threats are not distant hazards, but imminent security risks that must encourage us to re-think our approach to AI governance.

When following a course at Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute in 2019, Professor Allan Dafoe was already warning us against the “massive global and intergenerational externalities” of AI development and the “high leverage opportunities” it implies. The worst-case scenario he painted for us was grim: totalitarianism, conflict, human value erosion… but the solutions were also laid out: the governance of AI must be cooperative, founded on human values, and anchored in institutional mechanisms. Transparency and accountability are must-haves.

Concretely, the regulation of AI is nowhere near what it needs to be. EU lawmakers are preparing far-reaching legislations with the AI Act, Data Act, and Digital Services Act, but a lot of work remains to be done to match existing and progressing technology. For this reason, we should welcome the over-hyped yet valid open letter to pause the training of AI systems. The future of our societies and world information order may well depend on regulators’ and lawmakers’ capacity to act, and fast.

Written by Sophie L. Vériter

Global Society

With the advances of technology, we become more aware of how connected we are, as individuals, states, and continents, but also as a transplanetary community. This impacts how we imagine solutions to political, economical, and social challenges.

As an expert in international security and global affairs, I research how to create systems for a safer future. My articles delve into debates surrounding democracy, technology, and security.

I am currently working on more elaborate pieces that look into global information networks and how we can optimise them for public good.