Last week, I was invited to participate in the 11th edition of the World Forum for Democracy organised by the Council of Europe. This annual event joins individuals from more than 100 countries to discuss the future of democracy. This year’s guiding question was: does democracy equal peace? Over three days, a series of panels, labs, and talks covered a wide range of subjects, from journalism and education to open source intelligence and peace-building. Participants and speakers included government officials, civil society organisations, youth organisations, students, journalists, researchers, civil servants, activists, and political organisations.

In this article, I’ll share my key takeaways from the World Forum for Democracy. They are by no means a reflection of the event as a whole but a collection of my personal thoughts on the discussions that I attended, which were only a fraction of the whole range of debates and presentations organised. The forum was entirely recorded and every section of its programme can be watched here.

“Democracy is about people and it’s high time we put its social dimension back at its centre.”

Getting the Basics Right

The Forum started with a series of plenary discussions that presented key facts and figures about democracy. Without much surprise, speakers highlighted the decline in support for democratic regimes.

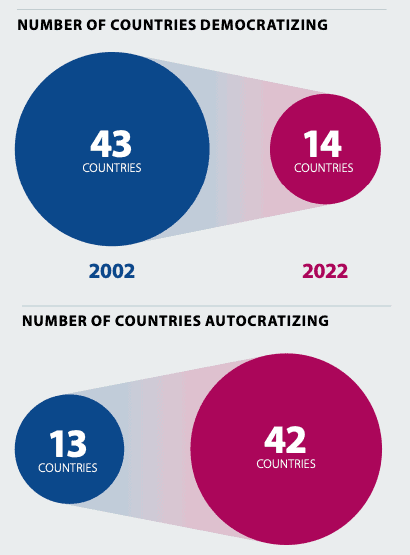

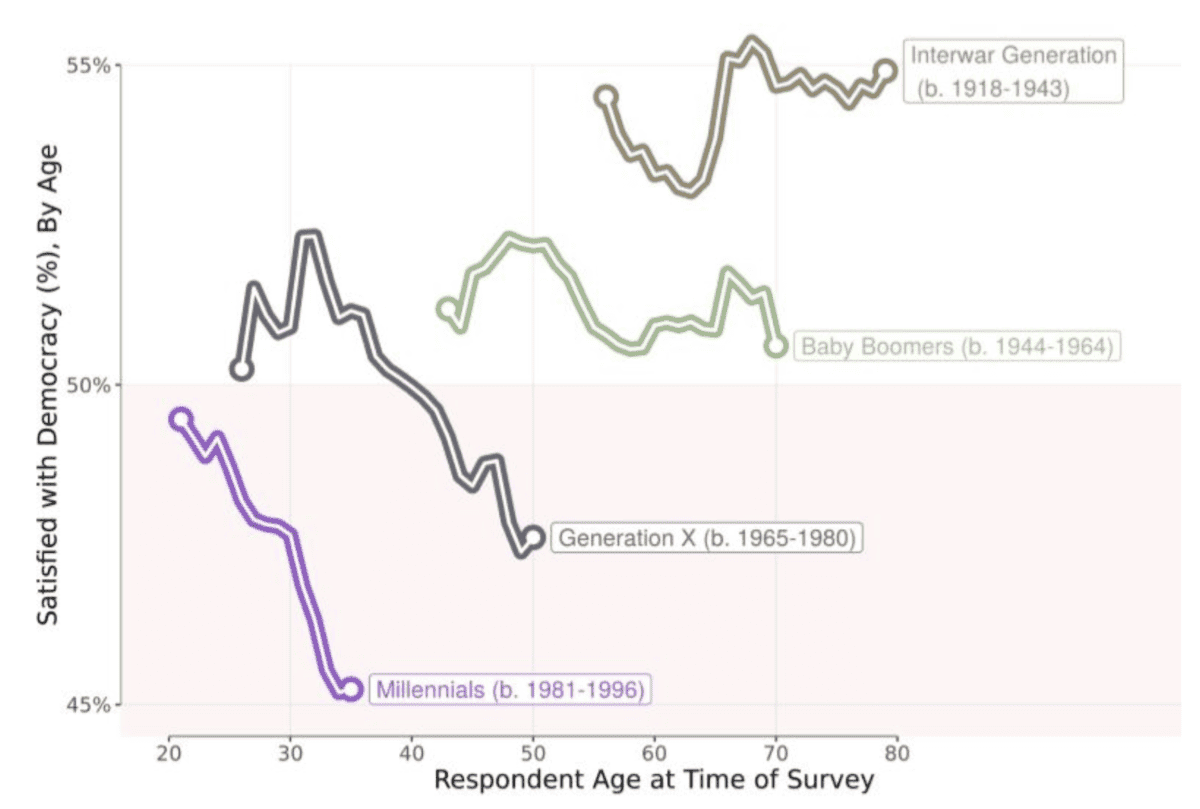

A study conducted at the University of Cambridge’s Centre for the Future of Democracy shows that, across generations, people are increasingly dissatisfied with democracy. Similarly, the V-Dem Institute shows that the number of states which an be considered as democracies are declining, while the number of autocracies keeps growing. Democracies have been associated with higher levels of peace and economic growth, according to our speakers from the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP). Nuance is however needed. Democracies may not usually be directly involved in violent conflicts (with notable exceptions such as Israel), they often actively fuel conflicts across the globe. As pointed out by Steve Killelea, Director of the IEP, some of the biggest arms exporters are democracies.

Furthermore, speakers highlighted the recent upsurge in violence around the world and the failure of institutions created in the aftermath of World War II, such as the United Nations, to address those conflicts and preserve democratic values. They noted the growth of intersectional global challenges fuelling one another, including gender inequality, climate change, and migration to name a few. I was particularly seduced by the intervention of Taeho Lee, Director of the Center for Peace and Disarmament of the People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy (PSPD) in Seoul, Korea. Mr Lee highlighted that governments have pursued democracy and peace through power, ignoring the voices of people. He invited us to see democracy as more than a concept, a set of theories, or institutions, but as an activity of the collectivity. Namatai Kwekweza (WELEAD) added that democracy manifests as different types of challenges, depending on the community where it is taking place. Democracy is indeed about people, and it’s high time we put its social dimension back at its centre.

"What About Us?" and the Purpose of Democracy

Participants had many opportunities to share comments and ask questions. I could not help but notice a common thread among those, namely the outcry of people whose nation or community had been affected by violence. Their only hope seemed to be the promise of peaceful democratic societies. The universality of human rights they defend. What I kept hearing was “What about us? What about my people? Have you abandoned us? Have you forgotten us?”. These questions highlight a painful truth: in the face of violent conflict, democracy is powerless. What is more, democracies have failed to make people heard and included, a very important element for modern security concepts such as ontological security (a sense of continuity and identity) and human security (understood at the human rather than state level). Hence, I had to ask in the plenary session on “democratic security”: What can we do to empower marginalised groups who face real life or death situations? This question entails the necessity to re-think the responsibility to protect so that it materialises in ways that individuals affected by conflict really need.

“If we claim that democracy isn’t the end goal, but certain ideologies are, we lose its essence.”

Another fundamental question came up in our plenary debate: is democracy the end goal? I think it should be. If democracy isn’t the end goal (instead, the objective could be to defend liberal values, for example), democracy is used to present one’s political agenda as being superior. Democracy has to be the end goal because that’s exactly what it is about: creating space for everyone to be welcome at the table, even if you disagree. Finding common ground. Evidently, this is only possible when democracy is paired with the protection of Human Rights and the Rule of Law, hence why they’re often grouped. When studying democracy typologies at Oxford University, I learned about consociational democracy as a “superior” type of democracy, one that is more stable and peaceful. At the World Forum for Democracy, I couldn’t help but think about what Arend Lijphart argued: cooperation, consensus, proportionality, and community should be at the forefront of democracy, as opposed to the will of the majority. Pluralism is essential. If we claim that democracy isn’t the end goal, but certain ideologies are, we lose its essence.

Double Standards and Moral Superiority

Many interventions from participants mentioned the undeniable existence of double standards in international institutions promoting democracy, not only in the political field but also judicial. The example of Russia being kicked out of the Council of Europe while Azerbaijan has been allowed to stay in, when both have violated human rights, instilled violent conflict, and present authoritarian tendencies, came up more than once. The false sense of moral superiority of democracies, who nevertheless also find themselves disrespecting human rights, fuelling conflicts, and committing war crimes (e.g. Israel), raised many eyebrows in the audience.

It’s just as important to look outside than to look within. As put by Alessandra Cardaci (Debating Europe), it’s like a relationship: you have to help your partner to grow while you keep working on yourself. The days in which Europe and the West could present themselves as morally superior have definitely come to an end, and it would be judicious to acknowledge our flaws and mistakes instead.

“Democracy cannot equal peace if we need wars to understand the value of Human Rights and the Rule of Law.”

During the second day of the World Forum for Democracy, we had the opportunity to attend a series of “labs” (initiatives presented by NGOs, activists, and researchers) and “talks” (hot topics discussed by experts and high-level policymakers). It was difficult to choose between the many fascinating subjects of discussion. At the lab entitled “Knowledge is Power”, I presented the initiative I co-developed with 8 other doctoral researchers, Level Up, which uses gamification to optimise participatory and deliberative democracy. Afterwards, I attended the talk “The Truth of War Crimes”, which discussed the role of journalism and open source intelligence in the prosecution of war crimes. We learned about the absolutely incredible work of Kathryne Bomberger (International Commission for Missing Persons), Eliot Higgins (Bellingcat), and Antoine Bernard (Reporters Without Borders), among others. However, what struck me was the choice of words of one journalist in the room, who explained that he felt thankful for Russia’s war in Ukraine because it helped him understand why he was doing what he was doing: “this will help us explain why it’s good to be European”. I almost had a heart attack.

This discourse perfectly illustrates the mistaken sense of “moral superiority” that many participants criticised. Democracies are not morally superior and it’s our collective responsibility to stop looking down on other countries and utilising their fate as a means to make sense of democratic states’ actions. Similarly, Noni Hlophe (Global Shapers Community) shared with me: who says there’s only one way of getting it right? Western models of democracies are not a perfect, one-size-fits-all approach. When will they start treating their partners as equal partners? The condescending tone needs to stop. Words matter. Most importantly, I found this journalist’s declaration profoundly sad. Did he truly need to see the death of innocents happen before his eyes for him to understand the meaning of his work? What would this reveal about our humanity, our empathy, if we had to continually see horrors to realise why we defend justice? Will we ever learn from History? Democracy cannot equal peace if we need wars to understand the value of Human Rights and the Rule of Law.

The Fourth Branch of Government

On the second day of the World Forum for Democracy, I joined a discussion on the “fourth branch of government”, a term coined by former Prime Minister George Papandreou which refers to the introduction of citizens’ assemblies as an additional pillar in the traditional power structure of states (judicial, executive, and legislative). As an active defender of participatory and deliberative democracy, I could not be more excited by this debate. The panel of speakers included Mr Papandreou himself (now Chair of the Council of Europe’s Sub-Committee on Democracy), Professor Byong-Jin Ahn (Kyung Hee University, Seoul), and Achilles Tsalas (Democracy & Culture Foundation, UK), among others. Their interventions alluded to the idea of longtermism in politics, i.e. prioritising long-term benefits as a moral imperative. The speakers insisted that “bold social action” and innovation was a prerequisite to make the fourth branch of government a reality in democracies.

However, I was disappointed to see the discussion running in circles. Some were claiming to use “innovative tools and methods” in their activities, but I could not see or hear anything I had not come across already. The reality is that thousands of researchers and civil society organisations have been working on developing innovative means of engaging citizens in democratic decision-making, gamification being a prime example. Dozens of other fantastic initiatives were presented in the labs throughout the World Forum for Democracy but, during this debate, their work and efforts were largely ignored. This situation illustrates the siloed co-existence of participatory and deliberative democracy efforts, where groups work on similar goals without talking to one another. This is a missed opportunity for he 4th branch of government to reach its full potential.

“Citizens’ hunger for more direct participation in democracy is not going anywhere, and it will keep on growing.”

The truth is it’s extremely complicated to keep track of grassroots initiatives; however, there is so much with can learn from them. This dilemma highlighted a crucial need to better keep track of such efforts, for example with a dedicated committee or organisatiom where lessons and ideas are pooled. The Civil Participation BePART is a great example of that; however, much more resources need to be invested in this work. It must include high-quality strategic communication, awareness-raising campaigns, and partnerships. Indeed, despite Mr Papandreou’s doubts about governments’ readiness to install this 4th branch of government, its spirit is already taking shape and grassroots initiatives will continue flourishing. Governmental actors will have to take a leadership role in this collective effort sooner or later. Citizens’ hunger for more direct participation in democracy is not going anywhere, and it will keep on growing.

Closing Remarks

In this article, I summarised my key takeaways from the 11th edition of the World Forum for Democracy. First, I highlighted the worrying trends when it comes to democracy and the risks that accompany the rise of autocracies worldwide for peace, security, and freedom. Building on the plenary debates, I argued that democracy should become a more social exercise. Second, I exposed democracies’ failure to make marginalised people included and heard, however universal they claim human rights to be. I contend that democracy should be an end in itself to preserve the plurality and inclusivity of debates. Third, I reflected on the double standards and mistaken sense of moral superiority often expressed by democratic regimes. It is essential that Western democracies establish equitable relations with their partners and defend their values before they are fundamentally threatened, if they want to remain a credible influence on the world stage. Finally, I called for a centralised effort to take stock of participatory and deliberative democracy initiatives and research. This is indispensable for the development of innovative solutions to the complex challenges which citizens are increasingly vocal about, especially their feeling of not being heard.

There is one more notable moment worth mentioning in this article. During a lab on freedom of expression, we were deeply shocked to learn that one of our speakers could not join us because he had just been killed in Gaza. Mohammed Al Jaja, a young journalist from Palestine, was supposed to share his experience through a live-stream due to the current war. Words cannot describe the feelings of horror and sadness I could see on everyone’s faces in the room. Beyond those incredibly distressing emotions, I hope that Mohammed’s story serves as a wake-up call. I hope that justice, accountability, and closure is given to everyone affected by violent conflicts which benefit no one but the (corrupted) global arms trade. This feels like a good moment to remind that three of the world’s largest arms exporters are Western democracies.

My condolences to Mohammed’s friends and family. May his soul rest in peace.

Sophie L. Vériter