Disinformation has become a popular subject of study and debate. A plethora of publications and policies have emerged, aiming to analyse and curb the negative consequences of unwanted communication. However, conceptual fuzziness, theoretical shortcomings, and intra-disciplinary outlooks have hindered progress when it comes to designing comprehensive policy responses. This blog post proposes to change the narrative about unwanted communication from being an external threat to be neutralised (”disinformation”, “propaganda”) to a structural set of malfunctions that we can treat from within (”information disorder”).

Conceptual Clarifications

Disinformation is “the intentional and systematic manipulation of information deceiving a target audience to cause public harm, generate profit and/or advance political goals”. It may be part of wider influence operations, led by public or private actors. The key terms here are intentional and systematic, but we are already running into an issue here: intent is subjective. What you may perceive as ‘intent to cause harm’ may well be interpreted by others as ‘intent to protect from harm’. Influence campaigns also heavily rely on ordinary folks to relay information. Research suggests that human individuals, not bots, are in fact the main drivers of false reports. However, people are often not aware that the information is false or half-true; they may not have the intention to deceive. Because determining intent is quite complex, scholars have increasingly preferred to use the term “misinformation”, which is incorrect or misleading information, but not necessarily deceptive or intentionally harmful.

"Influence campaigns also heavily rely on ordinary folks to relay information. Research suggests that human individuals, not bots, are in fact the main drivers of false reports."

Secondly, we frequently hear of disinformation and propaganda together. However, these concepts are different and should not be used interchangeably. Propaganda is information shared to promote a political cause – often, but not always misleading. It is, by definition, subjective. Both disinformation and propaganda are types of undesirable communication that can be understood as instances of information disorder, or “information pollution at a global scale”. They exacerbate polarisation, harm deliberative democracy by disrupting the public sphere, and have the potential to stimulate racially motivated violence. Both operate in an increasingly complex information ecosystem, with tangible and observable effects.

So, how did we get there?

Understanding Information Disorder

Whilst it is undeniable that information disorder has gained salience over the past decades, disinformation, misinformation, and propaganda have always existed. To understand contemporary information disorder, we have to delve deeper than the symptoms we observe today. Looking at historical and sociological factors is nonetheless not prevalent in early “disinformation studies”. Indeed, a lot of research and journalism on disinformation has focused on typology, actors, and policy, i.e. what strategies do we see? who is behind it? what should we do about it? I suggest – alongside other scholars – is to take a step back so that we can better understand the problem(s) we have in the first place.

First, it is essential to realise the technological and psychological factors inducing information disorder. An exponential amount of internet users worldwide get their information from very different sources and exist in echo-chambers that positively reinforce their beliefs because of algorithms (and sometimes legal frameworks) designed to show you what you already like and agree with, rather than a diversity of viewpoints. Humans are emotional beings constantly seeking novelty, certainty, and recognition, which are the star factors of online platforms. At the same time, the media ecosystem is unfairly competitive and prone to toxic behaviour. Tech giants (Meta, Twitter, Google, Microsoft, etc.) hold close to a monopoly on public debate and many businesses rely on advertising on their platforms, which capitalises on users’ attention and data. Therefore, they incentivise personalised, emotional, and sensationalist content – exactly what information disorder thrives in.

"I suggest - alongside other scholars - is to take a step back so that we can better understand the problem(s) we have in the first place."

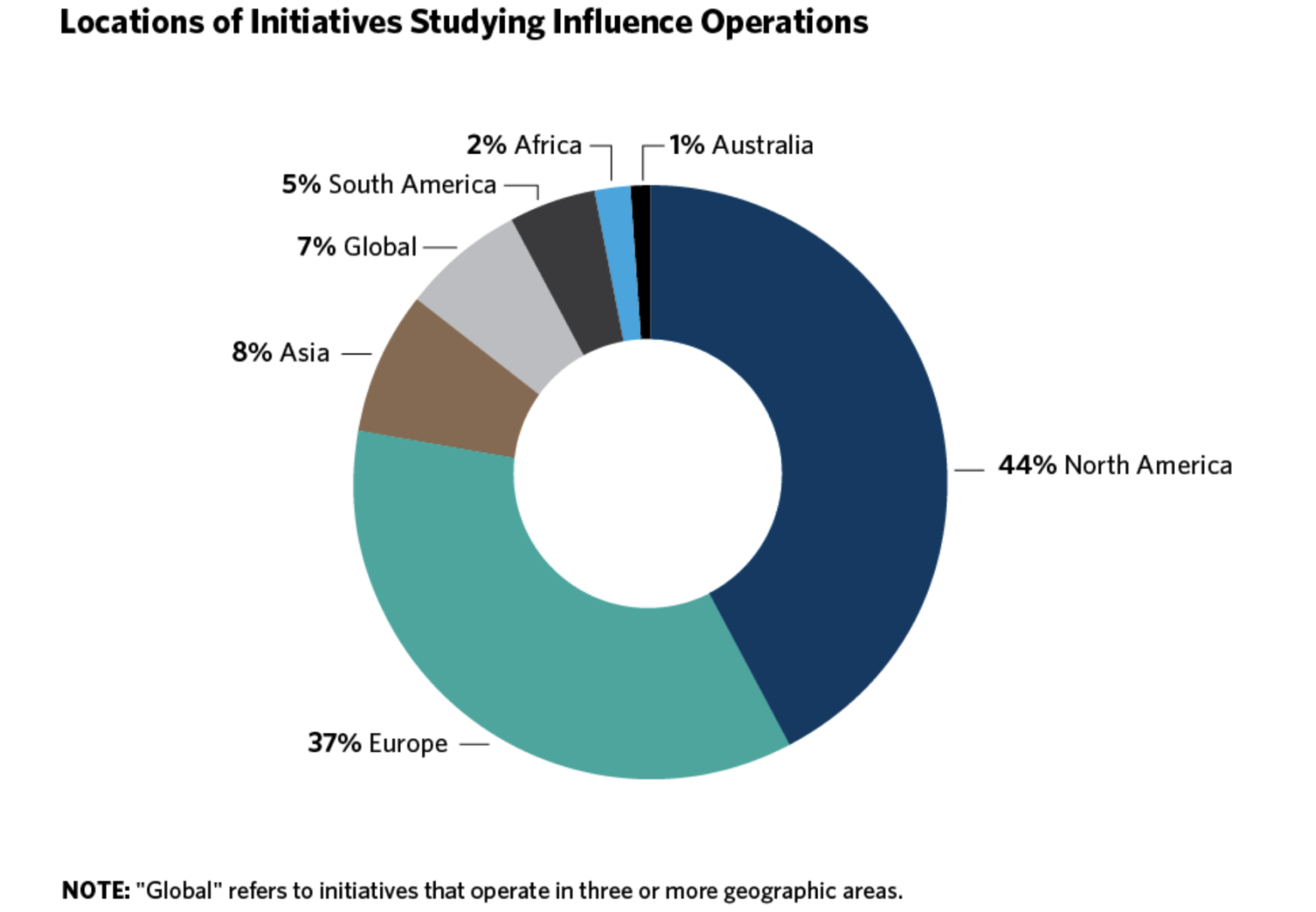

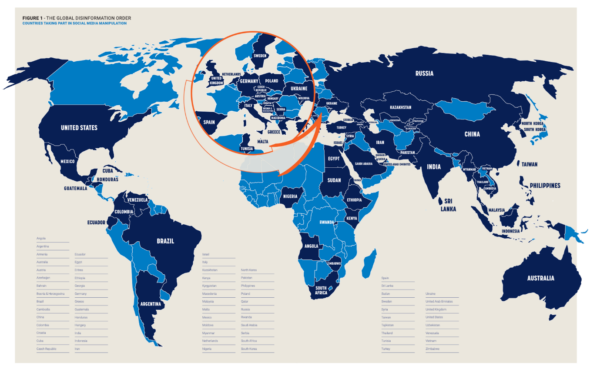

Second, a deeper understanding of information disorder implies moving away from actor-centred perspectives and closer to structural analyses. Disinformation studies have initially concentrated on pro-Kremlin disinformation. This is understandable because most of the studies on influence operations are located in North America and Europe (see Figure 1), where Russia is one of the primary sources of disinformation. However, already in 2019, Samantha Bradshaw and Philip Howard of the Oxford Internet Institute were showing that countries across the world are engaging in social media manipulation and raised specific concerns regarding China, India, Iran, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela – all using different strategies and narratives (see Figure 2).

To be sure, the West should address pro-Kremlin propaganda and disinformation, but it should also do so towards China, India, Iran, … and domestic sources. We have all heard of false or misleading reports spread by Western actors such as Donald Trump or Boris Johnson. In Serbia and Hungary, state actors have even utilised counter-disinformation laws to silence opposition. In sum, the problem is not actor-specific, it is structural. Presenting the problem as actor-specific is serving political goals. In other words, more than a ‘disinformation problem’, we are facing a global ‘information disorder’ problem in which certain actors strive more than others.

"More than a ‘disinformation problem’, we are facing a global ‘information disorder’ problem in which certain actors strive more than others."

Finally, a deep comprehension of information disorder entails a critical stance on the issues which are prominent subjects of disagreement and misinformation. The public has been consuming increasing amounts of information daily. Therefore, it can be more skeptical and less trusting, less agreeable. And this is a positive development, because the world as we know it is far from being perfectly organised. We need constructive criticism and diversity of ideas. However, this is also what makes information disorder powerful: it builds on existing pitfalls, myths, and grievances. When concerns are not addressed, they fester. Absolute trust in authorities, for most people, is not rational. Using the words of political scientist Pippa Norris, blind compliance raises as many issues as cynicism does, we should therefore praise skepticism. She refers to the Russian proverb “Доверяй, но проверяй”: Trust, but verify. In sum, information disorder is closely related to issues of public trust and debate, and how authorities approach them.

Altogether, these observations suggest that information disorder can be understood as a global sociological phenomenon. For this reason, I propose to change the narrative about unwanted communication from being an external threat to be neutralised (”disinformation”, “propaganda”) to a structural set of malfunctions that we can treat from within (”information disorder”).

Managing Information Disorder

Measures which aim to tackle information disorder were born within foreign and security policies, primarily aimed at foreign agents. However, it quickly became apparent that the problem emanated as much from the inside as it did from the outside. It’s uncomfortable to admit it, but in addition to toxic online platforms and foreign actors, domestic actors and information systems also fuel the information disorder (see the concept of participatory disinformation introduced by Kate Starbird).

There is only so much we can do to alter others’ thoughts and behaviour generating undesirable communication. It’s extremely difficult to change someone’s mind. Deterrence and debunking are not enough; research suggests they may even have adverse effects. What we can do, however, is build our societies’ resilience to manipulation in a healthier information order. That goes through civic education, critical thinking, media literacy, and support for quality journalism. Studies show that higher education is linked to more trust in media, which is linked to less disinformation exposure (see here, here, and here). We should thus empower scholars, diplomats, and journalists to better communicate their knowledge. Logical reasoning should be as sexy as conspiracy theories, but we should stay away from click-bait, emotional headlines.

"It’s uncomfortable to admit it, but in addition to toxic online platforms and foreign actors, domestic actors and information systems also fuel the information disorder."

We should also encourage reforms of the digital public sphere. What I mean by that is that, right now, online platforms act like a trans-border public sphere. We discuss and learn about socio-political developments from across the world, like the democratic fora envisaged by Ancient Greeks. However, today, these fora are primarily regulated by private actors who are conducting their business with the primary objective of maximising profit. The public sphere, however, should be public. There should be more transparency, accountability, competition, and pluralism. With new European regulations such as the Digital Services Act and the Data Act, the EU is setting the stage for this. But as long as information disorder poses problems somewhere, it will inevitably have consequences on actors in the West.

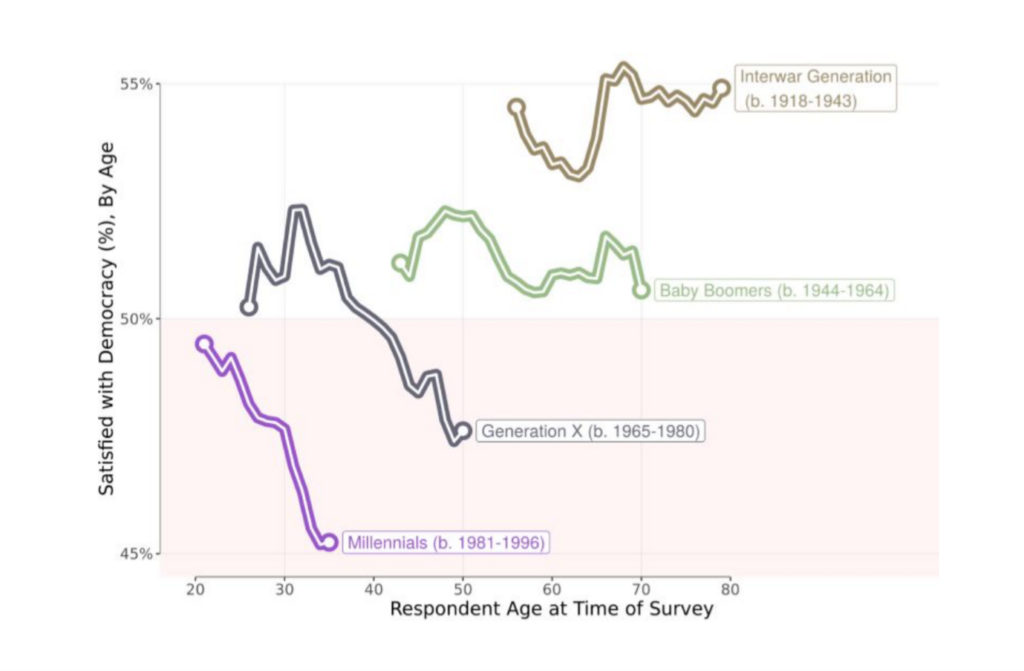

Finally, we should address the shortcomings on which information disorder is feeding. It’s easy to blame others, but let’s look into the mirror. According to a study conducted at the University of Cambridge, young generations across the world are disillusioned with democratic politics now more than ever (see Figure 3). Many Western democracies are showing concerning signs of corrosion and policy gridlock. Polarisation is rising and inequalities are deepening. In sum, in addition to treating the symptoms of information disorder, we must treat its causes by addressing it jointly with the drivers of public trust.

Conclusion

There is no easy fix to the information disorder. It requires comprehensive and far-reaching solutions concocted by inter-disciplinary teams with long-term outlooks. Unwanted communication will always exist, but we can improve our responses to it by isolating it from political goals, addressing the structural factors which induce it, understanding the psychology and ideology which underpin it, and embracing it as an opportunity for dialogue and progress. I choose to see information disorder as a positive development. Yes, it’s a serious challenge, but as all challenges, it provides a choice: to feel threatened, to be defensive, and deny criticism… or to embrace it as an opportunity for better decision-making, persistence, and growth.

Transitioning to a healthier information order requires both individual effort and systemic change. As individuals, we should strive to open our social circles beyond what’s comfortable and lean into difficult conversations with the desire to understand the concerns of other parties. Businesses should consciously design their strategies and adopt diversity of leadership. Journalists should stay away from sensationalist content and uphold high ethical standards. Scholars ought to communicate their knowledge widely in an accessible manner. Last but not least, public actors such as policy-makers and diplomats must welcome disagreement and promote transparency, accountability, competition, and pluralism in the public sphere. That means, above all, alleviating the grip that tech giants have over online communication and promoting media literacy and critical reasoning across all age groups.

Written by Sophie L. Vériter

This essay was first published on The Hague Journal of Diplomacy Blog on 2 March 2023.

Key Readings on Information Disorder

- The Problem With Defining “Disinformation” by Gavin Wilde (Carnegie)

- Mis- and disinformation studies are too big to fail: Six suggestions for the field’s future by Chico Camargo and Felix Simon (Misinformation Review)

- Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making by Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan (Council of Europe)

- European Democracy and Counter-Disinformation: Toward a New Paradigm? by Sophie Vériter (Carnegie)

- Industrialized Disinformation: 2020 Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation by Samantha Bradshaw, Hannah Bailey & Philip N. Howard (Oxford Internet Institute)

Global Society

With the advances of technology, we realise how connected we are, as communities, states, and continents,… but above all as individuals communicating across borders. This impacts the solutions to our political, economical, and social challenges.

My vision of a global society is one that values life-long learning, empathy, and inclusivity. These values are crucial for a sustainable future on earth. Looking at the state of democracy and information disorder, it becomes obvious that a multi-level mindset shift is essential to heal the way we’ve conducted international relations. It’s high time for the global transformation we need.