Unveiling Musk’s X Exit from the EU Disinformation Code

Introduction

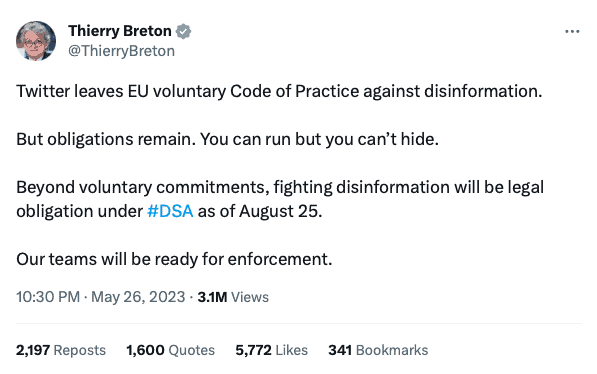

In May 2023, the tech and European policy communities were caught off guard when European Commissioner Thierry Breton made a startling revelation: Twitter, now operating under the rebranded name “X”, had chosen to withdraw from the EU’s Code of Practice on Disinformation. This unexpected move swiftly ignited two crucial inquiries: why did Twitter opt for this course of action, and what ripple effects will it set in motion? In this article, we embark on a comprehensive exploration of these pivotal questions. First, we offer an insightful glimpse into the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation—a foundational document that has seamlessly integrated into the Digital Services Act (DSA) since its enactment in November 2022. Furthermore, we scrutinise the specific provisions within the Code that have led to the recent divergence of Twitter’s strategies. Ultimately, we shed light on the implications of Twitter’s non-compliance with these regulations and the potential ramifications for the platform’s future.

The Disinformation Code of Practice, in a Nutshell

The 2022 Code of Practice on Disinformation is the result of renewed efforts by the European Commission to encourage online platforms, fact-checkers, and advertisers to commit to more comprehensive and effective measures for combatting misinformation and disinformation online. For those still grappling with the distinction between these terms, you can refer to my earlier article on the subject here. The current content of the Code has evolved from its original 2018 version through several rounds of negotiations among its signatories. These discussions aimed to establish a robust set of practices that limit users’ exposure to misleading information and influence operations in the digital realm. Signatories span a wide spectrum, from tech giants like Microsoft and Meta to more specialised platforms such as Clubhouse and fact-checking organisations like NewsGuard. All of them pledge to implement a comprehensive set of measures designed to protect EU citizens from undue online influence.

It’s no secret that online platforms have been hotbeds for influence operations and disinformation campaigns, both domestically and from foreign sources, impacting European politics and society. The Code of Practice represents one of the European Commission’s tools to curb these issues while safeguarding EU citizens’ freedom of speech and privacy. Interestingly, despite being presented as a voluntary ‘soft law’ document that signatories can opt in or out of, failing to adhere to its provisions can have substantial consequences. This is because the Code has been integrated into the DSA, which took effect in November 2022.

The DSA imposes distinct legal obligations on digital service providers based on their size. For Very Large Platforms (VLOPs) and Very Large Online Search Engines (VLOSEs), which boast at least 45 million active users, stricter regulations apply to empower and safeguard their users. Twitter, alongside industry giants like Google, TikTok, Snapchat, LinkedIn, and others, falls into this category. As outlined in Article 35 of the DSA, VLOPs and VLOSEs must mitigate misinformation risks in accordance with the Code of Practice. Non-compliance with the DSA can result in fines of up to 6% of annual turnover, potentially translating to around $300 million for “X”, along with a European-wide ban in the event of repeated violations. VLOPs, including “X”, are required to comply with the DSA by August 25, four months after their designation.

Signatories' Commitments: What's Troubling Elon Musk?

The Code of Practice outlines a series of commitments that signatories are encouraged to uphold, elaborated over 48 pages. These commitments span nine categories: ad placements, political advertising, integrity of services, empowering users, empowering the research community, empowering the fact-checking community, transparency, monitoring, and cooperation with the Task Force responsible for the Code’s implementation.

Advertising Transparency

First, commitments pertaining to ad placements demand that signatories defund disinformation and implement more stringent rules for advertising. This serves a dual purpose: preventing individuals and organisations from profiting from misleading online content and preventing such content from being artificially promoted. Moreover, the Code requires signatories to establish a shared definition of political advertising and disclose their policies in this regard. Political advertisements must be distinctly labeled and provide users with information such as the sponsor, ad duration, and associated costs.

These comprehensive rules primarily stem from concerns regarding the use of personal data in political ads, as exemplified by the Cambridge Analytica scandal which violated user privacy. The EU now insists on full transparency for political ads to prevent foreign interference in electoral processes. This section may pose challenges for Twitter, among other VLOPs, as the requirements are extensive and could necessitate a substantial platform redesign. In fact, Meta is contemplating a complete ban on political advertising in Europe to sidestep the complexities of compliance.

However, it’s important to note that the European political advertising market is relatively small compared to the US market. Consequently, Twitter would not suffer a significant revenue loss if it decided to do the same. Additionally, Twitter has gradually shifted from an ad-based revenue model to a subscription-based system with “Twitter Blue,” offering users enhanced features for a monthly fee of 11€. Therefore, aligning with the Code of Practice in relation to political advertising is unlikely to be financially burdensome for Twitter.

Integrity of Services

Second, the Code of Practice addresses commitments related to the integrity of platforms’ services, encompassing their transparency, collaboration, and policies regarding misinformation. It mandates that VLOPs establish clear policies for tackling misinformation, including the handling of fake accounts, bots, fabricated engagement, and hack-and-leak operations. VLOPs are also required to measure the impact of such deceptive behavior on their platforms. This particular aspect could be unsettling for Twitter, which has faced suspicions about the extent of fake user accounts on its platform, with estimates ranging from 5% to as high as 80% of users being potentially fake.

Furthermore, the Code of Practice obliges VLOPs to permit the use of anonymous and pseudonymous accounts and services, directly conflicting with Twitter’s recent direction. Twitter’s CEO, Elon Musk, has expressed intentions to “authenticate all real humans” on the platform. However, the cybersecurity community has raised alarm bells concerning the high risks associated with such endeavours, most recently following the announcement that all X Blue users should send a selfie and a copy of their ID to a verification company based in Israel. This divergence from the Code’s requirements may present a significant challenge for Twitter when implementing the DSA.

Empowering users, researchers, and fact-checkers

Third, the EU Disinformation Code of Practice imposes a series of requirements to empower users, fact-checkers, and researchers in identifying and reporting misinformation on VLOPs. Signatories must not only develop sophisticated and transparent policies but also adapt their platform’s design to minimise the impact of false and misleading content. One of the Code’s key areas of focus pertains to recommender systems, which determine the content displayed in users’ feeds. These systems must guide users toward authoritative sources for topics of high public interest, while also allowing users to customise their preferences. Additionally, VLOPs must promote media literacy and critical thinking through awareness campaigns and provide tools for assessing content accuracy and authenticity, such as independent fact-checking indicators.

These provisions could pose challenges for Twitter, given its adoption of a crowdsourced fact-checking system known as “Community Notes”. However, questions have arisen about the effectiveness of this program, as the majority of Notes (approximately 92%) never progress to the public stage. To be made public, Notes must receive favourable ratings from users across the political spectrum, which explains why most Notes offering context to questionable statements remain unpublished. Twitter’s former Head of Trust and Safety has referred to this as a “failure” for its inability to address harmful political and politicised content. Nevertheless, the system does seem to prove effective in flagging scams and addressing pop culture controversies.

Adequate Resources

Finally, the Code repeatedly emphasises the allocation of adequate resources to ensure effective implementation. VLOPs are required to provide regular reports to the European Commission detailing their efforts against misinformation and must bear the cost of audits. It also mandates collaboration among VLOPs to establish uniform standards and greater accessibility for research and fact-checking communities, with financial contributions being a potential avenue. The creation and regular updating of a Transparency Center are also required to enable users to access pertinent information on the Code of Practice’s implementation.

For Twitter, this might pose a serious problem, considering its financial challenges and recent layoffs of employees focused on research and safety. Shortly before announcing its withdrawal from the Code of Practice, Twitter failed to submit a complete report to the European Commission, displaying incomplete data and missing sections. Additionally, Elon Musk has demonstrated a reluctance to cooperate with competitors, blocking content from the newsletter platform Substack and engaging in legal disputes with Meta, a key competitor.

Analysis

A close examination of the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation reveals that Twitter or “X” does, in fact, align with the majority of the Code’s commitments aimed at protecting user rights and privacy. Over the years, Twitter has implemented clearer policies and innovative systems to combat the impact of misinformation on its platform, such as the introduction of Community Notes. Only a few grey areas remain, primarily centred around third-party oversight. Twitter appears to resist external scrutiny of its practices, potentially depriving users of a trustworthy experience. One particularly contentious point is the Code’s emphasis on independent fact-checkers, which Twitter appears to bypass entirely. The Code however sets rigorous criteria for fact-checkers to be deemed independent, including financial transparency, creating a reliable framework for third-party assessment.

Since acquiring Twitter, Elon Musk has presented himself as a “free speech absolutist.” However, his refusal to comply with the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation suggests that Musk should rather be viewed as a “digital dictator.” Any legal expert would understand that a crucial element in protecting human rights, such as freedom of speech, lies in establishing boundaries for these rights. “My liberty stops where yours begins” said John Stuart Mill. In a world where AI-generated disinformation can be more convincing than human-generated content, it becomes essential to erect barriers to preserve not only individual freedom of expression but also rights to equal treatment, privacy, free and fair elections, and the institutions that safeguard these rights.

Finally, it is increasingly apparent that Musk’s ambitions for Twitter extend beyond mere business ventures. His vision for “X” encompasses creating an “everything app” for transactions and a platform for citizens to exchange information and engage in social and political debates —an admirable objective in theory. However, if Musk is serious about making Twitter a representation of societal voices and connections, substantial progress is required in terms of platform management. His recent actions suggest that he aspires to play a political role, particularly in the US. However, a core feature of democratic politics, where human rights flourish more than in other systems, is the separation of powers and checks and balances among independent entities. In a democracy, third-party scrutiny is a fundamental component and should be welcomed as an opportunity for improvement. Instead, Twitter’s recent management decisions portray constructive criticism of its functioning as censorship.

As argued elsewhere, while it is a valid concern that strict content moderation rules may lead platforms to over-delete content to avoid legal liability, it isn’t a wise decision to restrict inappropriate content to strictly illegal behaviour (which has been Musk’s stance so far). A functional balance can be found, and the Code of Practice provides a strong basis for it. In particular, its commitments regarding critical thinking and digital media literacy constitute a fundamental improvement in how the EU has dealt with misinformation. A sustainable solution to information manipulation must indeed foster public trust with a healthy dose of skepticism.

Conclusion

Twitter, now known as “X,” has withdrawn from the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation, raising questions about its owner Elon Musk’s motivations and potential consequences for the platform. The Code, integrated into the Digital Services Act, imposes obligations on Very Large Platforms (VLOPs) and Very Large Online Search Engines (VLOSEs) to combat mis- and disinformation. This article has highlighted the commitments within the Code that could pose challenges for Twitter, including advertising transparency, integrity of services, empowerment of users, fact-checkers, and researchers, and the allocation of adequate resources. Despite aligning with most Code commitments, Musks’s reluctance to comply with certain provisions casts it in a contentious light, in particular because it clashes with the democratic principles and free speech which he claimed to protect. If Musk truly wants “X” to be a safe haven from undue influence, it will be necessary to grant some independent third-parties the capacity to review the platform’s functioning. His vision for “X” as an “everything app” hosting a range of digital interactions from transactions to political debates also faces scrutiny in light of these developments as a potential “regulatory nightmare“.

The consequences of Twitter or “X” not complying with the Code of Practice on Disinformation and the associated DSA can be severe, encompassing financial penalties (up to 6% of annual revenue), legal actions, reputation damage, and a potential ban from the European market. These consequences underscore the importance of tech companies like “X” taking regulatory obligations seriously and working to align their practices with evolving legal frameworks. As the fast-approaching deadline of August 25th for VLOPs and VLOSEs to conform to the DSA looms, the repercussions of Musk’s uncertain manoeuvring will soon come into sharp focus.

Written by Sophie L. Vériter