In May 2024, I had the opportunity of staying in Oslo for a residency at the ARENA Centre for European Studies thanks to a scholarship from the RENPET Network, an alliance of ten universities fostering research on EU foreign policy. Under the supervision of Dr Helene Sjursen, I worked on a research project that seeks to unveil the socio-political context of the adoption of the ban of Russian media outlets RT and Sputnik in the EU in March 2022. This project fits into my doctoral dissertation on the development of EU policies addressing disinformation and foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI). Joining the University of Oslo and exchanging with the fantastic community of scholars at ARENA was helpful to advance my empirical research as well as refine the theoretical contribution of my latest project.

In this blog post, I outline the research project I worked on while in Oslo and explain why it was useful to conduct interviews with Norwegian government officials. I then place it in the broader framework of my doctoral dissertation, highlighting the key questions it seeks to answer as well as its theoretical and practical implications. Finally, I reflect on the wonderful experience I had in Oslo and share some of my cultural and sightseeing highlights from the trip.

My research project on the ban of RT and Sputnik

In March 2022, the Council of the European Union introduced restrictive measures in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that suspended the broadcasting of Russian media Sputnik and RT in the EU. The sanctions (Council Regulation 2022/350) are in effect until the war “is put to an end” and Russian state-sponsored media “cease to conduct disinformation and information manipulation”. Despite the unprecedented scope of these restrictions, the Court of Justice of the EU found that they were legal, proportionate, and fell within “the objective of safeguarding the values of the Union, its fundamental interests, its security, its integrity and its public order”.

This research project, which constitutes one article as part of my article-based PhD thesis, explores the socio-political grounds that have led to those measures. They are puzzling, first, because of their restriction on freedom of expression and information and, second, because the regulation of media content is a competence usually reserved to Member States. The paper uses collective securitization theory to explain why EU Member States agreed on the ban. Specifically, it seeks to unveil states’ agency in this process. To do so, I use an inter-disciplinary approach rooted in qualitative methods analysing varied primary sources in triangulation, including interviews with policy-makers, legal texts, speeches, and inter-governmental papers.

It was particularly useful to be in Oslo because Norway, which traditionally aligns with the EU’s sanctions despite is non-EU member status, declined to implement the ban of RT and Sputnik. This is particularly unexpected given that Norway shares a border with Russia. However, the government deemed that the restrictive measure was incompatible with its national constitution, which is highly protective of freedom of expression. Mari Vesland, Director of the Norwegian Media Authority, explained: “In the Norwegian context, we see media literacy as the best tool against Russian propaganda”. It was thus extremely useful to be in Oslo to conduct interviews with government officials who could share more about their logic of interaction, which contrasts with that of EU member states and thus highlights decisive factors in the adoption of the measure.

My doctoral thesis: Countering Disinformation in the EU

The ban of RT and Sputnik is just one measure among the EU’s policy toolbox to counter disinformation and foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI). This has grown from a quasi-inexistant concern to a high priority in EU foreign policy. New units, financial instruments, and regulations have emerged in the last decade to address the threat that European political actors perceive from disinformation, mainly the potential undue influence it could have on its democratic processes (election interference) and institutions (public distrust).

My doctoral dissertation seeks to answer the following questions. First, why did counter-disinformation policies emerge the way they did in the EU? It is surprising that common policies first emerged as part of the Common Foreign and Security Policy in 2015, given the divided political context on this issue at the time. My first study, published in the Journal of Common Market Studies, reveals the remarkable role of Latvia in gathering consensus on this issue. Second, how have European counter-disinformation policies evolved since their origins? EU policies first originated in the foreign and security domain (e.g. the East StratCom Task Force in the EEAS) but then extended to the internal market, particularly digital policies (e.g. the Code of Practice on Disinformation). Third, why do some counter-disinformation policies seemingly contradict fundamental rights? The case of the ban of RT and Sputnik shows that the securitisation of disinformation has made the adoption of drastic and expansive measures possible in the EU.

Studying the development of EU policies against disinformation highlights two key implications. First, from a theoretical perspective, it offers insights into small state influence and collective securitization. Second, from a practical perspective, its findings about information governance, particularly its framing and political underpinnings in Europe, provide valuable lessons for the future of this policy field. In the last chapter of my thesis, I present new policy outlooks derived from complex network theory, an inter-disciplinary approach derived from theoretical physics.

How I fell in love with Oslo

It was absolutely wonderful to be in Oslo in May 2024, not only to conduct interviews and exchange about my research project with new colleagues at the ARENA Centre, but also to learn about Norwegian culture. As said by one of my interviewees, I “hit the weather jackpot” while being there, since the temperatures stayed around 25 degrees Celsius for the entirety of my stay – a rare occurrence for that time in Oslo. It was just perfect to walk around the city and discover its many charming neighbourhoods and history. The city is hilly and scattered with greenery and colourful houses, which makes it a particularly beautiful sight.

I had the chance of being in Oslo on 17 May, which is national day. I had never seen anything quite like this before! On that day, children and students parade through the city with music and encouragements from the public from early morning till the afternoon. What I found the most amazing was how beautiful everyone looked. On national day, the whole city comes out with their best clothes, hair, make-up, and shoes, ready to cheer and party. Most people wear a traditional attire or a very fancy dress or costume. It was a very unique sight to see! So many flags! The atmosphere was festive and joyful and everything was very well organised and proper, the epitome of a Scandinavian celebration. I was also kindly invited to join a Norwegian folklore dance show and practice organised by the university for PhD students, which was a lovely experience.

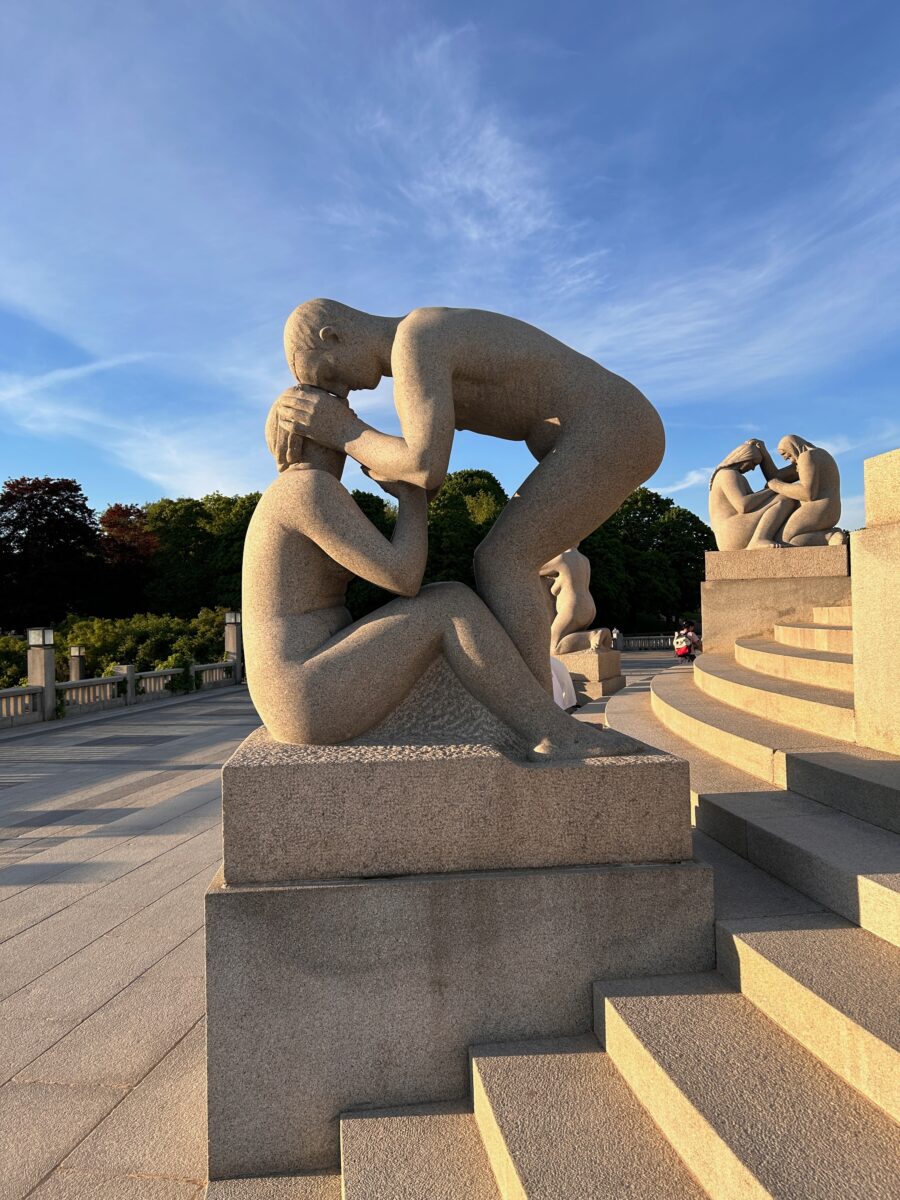

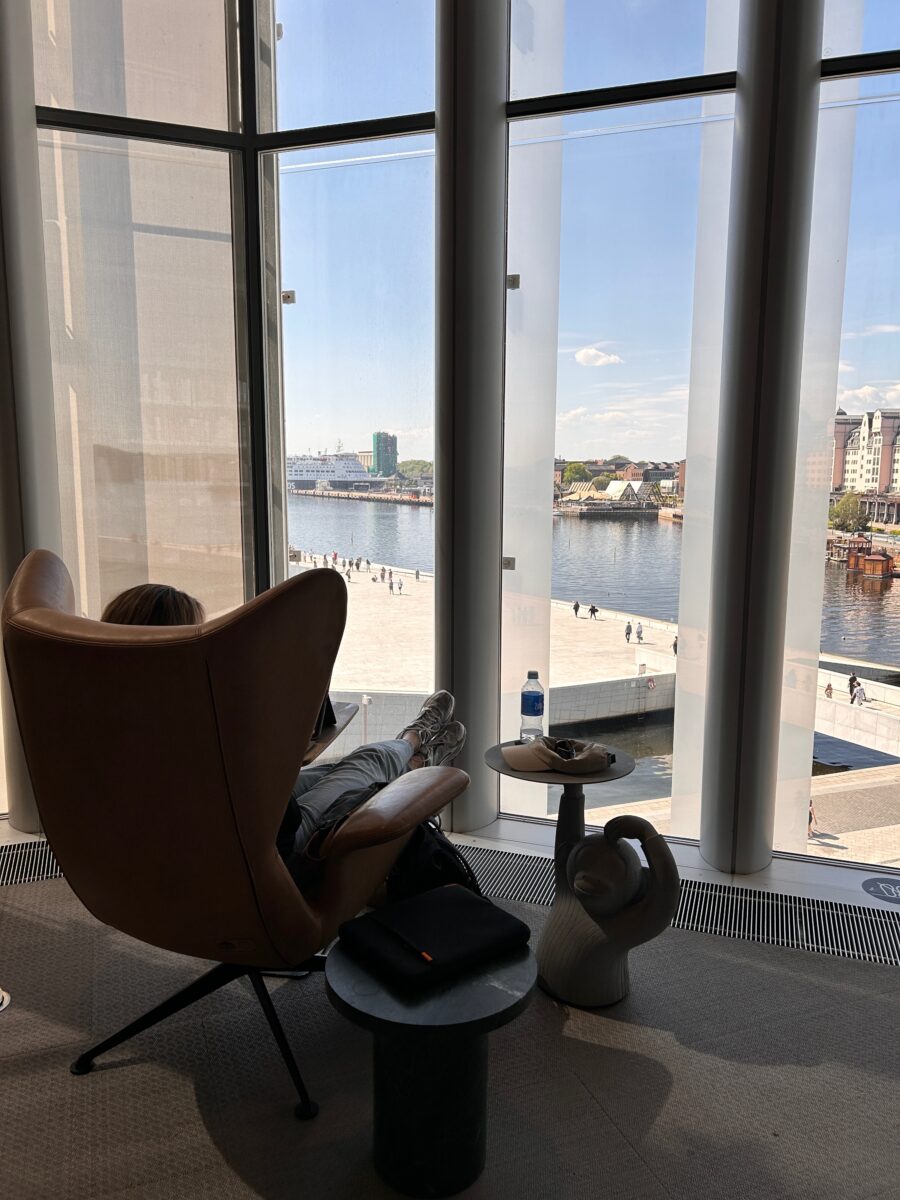

In Oslo, I particularly loved the areas of Uranienborg and Grünerløkka, where I found the architecture to be the most picturesque. Uranienborg is perfectly located between the two main parks of Oslo: Frognerparken, an large open-air museum where sculptures of the artist Gustav Vigeland are exposed, and Slottsparken, a lovely set of gardens surrounding the Royal Palace. I also loved visiting the nearby island of Hovedøya, accessible by public ferry. A peaceful escape from the city. Other inevitable landmarks are the Akershus Fortress and the Opera House, which sits on the harbour surrounded by floating sauna rooms. Next to it is the public library, Deichman Bjørvika, a must-see for anyone loving to learn and craft: public libraries in the Nordic and Scandinavian countries not only hold a wide variety of books but also a myriad of tools anyone can use such as instruments and recording studios, 3D printers, computers, sewing machines, and more!

My experience in Olso was one I’ll never forget and I am thankful for the RENPET Network to have given me the opportunity to fall in love with this beautiful city. I am also grateful for the warm welcome I have received at the ARENA Centre for European Studies, which made my stay even more delightful.

Sophie L. Vériter

About the author

Sophie Vériter is a PhD candidate in Security and Global Affairs at Leiden University (Campus The Hague), where her research examines the latest developments in misinformation and counter-misinformation policies, in particular in Europe. Sophie is broadly interested in the relationship between information, technology, and democracy, and the narratives that surrounds information governance. She has been a Europaeum Scholar as well as a Fellow at The Hague Program on International Cyber Security and the Global Governance Institute. From 2016 to 2018, she designed and launched the ‘Young European Ambassadors’ initiative for the EU’s largest public diplomacy campaign (EU OPEN Neighbourhood). Sophie holds a MPhil in Politics (Merit) from the University of Oxford and a BA in International Affairs (Summa Cum Laude) from the Brussels School of Governance.