In the aftermath of Ukraine’s Euromaidan Revolution of 2013-14, pro-Kremlin propaganda reached unprecedented levels. It started spreading confusion and distrust in Western institutions more easily and rapidly than ever before. Latvia, a small nation formerly part of the Soviet Union and home to a significant ethnic Russian minority, perceived an acute threat to European stability and convinced the entire European Union (EU) to take action. This article explores how Latvia managed to influence EU policy-making, providing valuable lessons on small state influence in the EU and important insights into the origins and framing of counter-disinformation policies in Europe.

Background

In 2015, Latvia persuaded other EU member states to create the East StratCom Task Force, an influential unit within the European External Action Service (EEAS) that conducts strategic communication activities for the eastern neighbourhood. It is best known for its EUvsDisinfowebsite, which debunks pro-Kremlin propaganda, but it has also significantly influenced EU external and internal policies by lobbying for stronger measures against disinformation (i.e. intentionally misleading or false information; see here for a quick distinction between key concepts). Almost a decade later, disinformation has become one of the top threats on the EU’s security and defence agenda. Most recently, the EU banned Russian media outlets Sputnik and RT from broadcasting on its territory and has continued to add more news outlets to the list.

One could argue that these developments were inevitable, given the rising tensions on the EU’s eastern borders and the current Russo-Ukrainian conflict. What is surprising, however, is that a collective solution was favoured over national ones considering the divergent interests of EU member states at the time and the requirement for unanimity in EU foreign policy decisions. MacFarlane and Menon arguethat, in the aftermath of Euromaidan, the varied histories and interests of European states resulted in a spectrum of positions ranging ‘from the obsessive to the disinterested’. Despite this divisive context and its limited capacity as a small state, Latvia managed to see its proposal for the creation of a new unit approved and implemented within six months. Since then, the team has had a visible impact on EU public diplomacy and secured more funding than other similar units in this field. Olsson et al. characterised this as ‘the most institutionalized issue-specific efforts in the history of EU public diplomacy’.

So, how did such a small state manage to have such a notable influence? Drawing on 30 interviews with policymakers, this article tells the remarkable story of how Latvia took the lead in shaping EU counter-disinformation policy.

From Niche Expertise to Leadership

Given its proximity to Russia, Latvia has been a prime target of Kremlin-orchestrated cyber attacks and influence operations. The Baltic states had warned for decades about the effects of its propaganda model on the European public sphere. By contrast, when Russia illegally annexed Crimea in March 2014, many EU diplomats and intelligence officials were taken by surprise. There was “a lot of confusion” and “nobody wanted to take a position” recounted a senior EEAS official who handled the crisis at the time.

Weeks earlier, Latvia had established the NATO StratCom Centre of Excellence in Riga (which it funds to 85%). It also attempted to shut down newly established local branches of Russian media outlets but encountered EU barriers designed to protect media freedom. A Latvian diplomat explained: “We realised we can’t do this because there are EU regulations, there are these mother companies registered in the UK or Sweden, and we cannot do anything. So, we realised that you have to work [at the] EU level”. This marked the start of a coordinated lobbying effort to counter disinformation despite challenges related to competences and legal basis.

Building on the heightened sense of insecurity spurred by Russian foreign policy and propaganda, Latvia developed a strong expertise in strategic communication. This expertise enabled it to influence policy developments in EU circles. Thanks to the expertise developed by its nationals and the credibility boost brought by its NATO Centre, Latvia naturally emerged as a leader in the field. Upon assuming the Presidency of the Council in January 2015 (a role that rotates among EU member states every six months), Latvia seized this opportunity to push proposals for joint action. It initiated discussions and fostered compromise among EU representatives, convincing other states of the urgent need for a coordinated response and garnering a growing coalition of supporters.

The Art of the Possible

Over the next six months, Latvia strategically steered discussions while chairing Council meetings with representatives from other EU member states. When asked who led the lobbying efforts for counter-disinformation measures, a civil servant who attended those discussions plainly answered: “Latvians.” The topic was raised at “almost at every meeting, as a subject of discussion of the agenda or as intrusion into discussions which would be either geared at Russia or Ukraine” explained a diplomat who followed the process closely.

Latvia and its allies gradually convinced others of the urgency of the situation and the need for a dedicated unit to monitor, analyse, and debunk pro-Kremlin propaganda. A series of misinformation scandals (e.g. regarding the downing of flight MH17 and the terrorist attacks in Paris) helped bring key member states on board. They remained particularly flexible during the negotiations to ensure an outcome: “You have to leave things open, so that you can actually negotiate. (…) It’s easier to promote something when it’s vague” explained a Council representative. In June 2015, the East StratCom Task Force was created and the EEAS published its Action Plan on Strategic Communication, laying the first foundation of a European counter-disinformation policy.

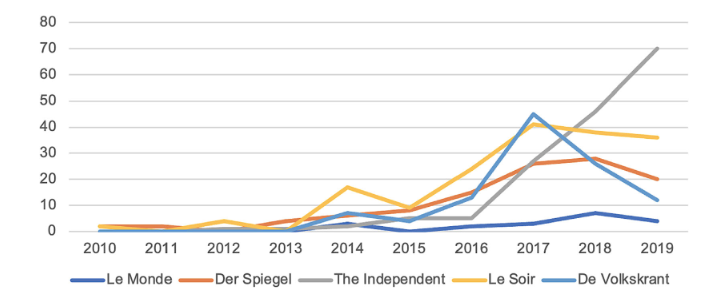

Afterwards, the coalition made of Latvia and its strategic allies continued lobbying for more resources as disinformation became a more prominent issue in the media, illustrated in Figure 1 above. Their representatives in Brussels, along with the members of the East StratCom Task Force, pushed for EU funding for the team. In 2018, the European Parliament allocated them €1.1 million from its Preparatory Action budget designed to test new initiatives before they have a legal basis. Thanks to renewed initiatives by the European Parliament, the team’s budget rose to €3 million in 2019 and €4 million in 2020. The EU’s counter-disinformation policies now go far beyond the foreign and security realm, with extensive efforts implemented internally by the European Commission, for example through the Digital Services Act.

Conclusion

Latvia’s story offers valuable lessons for small states seeking influence within the EU. First, the Presidency of the Council presents a unique opportunity to set the agenda and garner support for initiatives. Second, collaborating with representatives in other institutions like NATO and the European Parliament enhances legitimacy and impact. Third, linking proposals to current events and public concerns increases the chances of success, underscoring the role of the media and public pressure as instruments for driving policy change. Lastly, this case shows that the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy can serve as an entry point for broader influence on EU policies, including domestic ones.

Latvia’s leadership not only resulted in the creation of the East StratCom Task Force, which remains the best-funded and most influential EU body tackling disinformation, but also fundamentally shaped the EU’s approach to this challenge as a security threat. Without Latvia’s lobbying efforts, it is uncertain whether the EU would have developed such a comprehensive counter-disinformation toolkit by the time Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. However, further research is needed to explore the consequences of this framing for peace and democracy in Europe.

Sophie L. Vériter

This piece, first published in OxPol, is based on a longer academic article published in the Journal of Common Market Studies in March 2024, openly accessible here.

About the Author

Sophie L. Vériter is a PhD candidate in Security and Global Affairs at Leiden University (Campus The Hague), where her research examines the latest developments in misinformation and counter-misinformation policies, in particular in Europe.

Sophie is broadly interested in the relationship between information, technology, and democracy, and the narratives that surrounds information governance. She has been a Europaeum Scholar as well as a Fellow at The Hague Program on International Cyber Security and the Global Governance Institute.

From 2016 to 2018, she designed and launched the ‘Young European Ambassadors’ initiative for the EU’s largest public diplomacy campaign (EU OPEN Neighbourhood). Sophie holds a MPhil in European Politics and Society (Merit) from the University of Oxford and a BA (Summa Cum Laude) from the Brussels School of Governance.